Picture

Book contains nineteen horizontal spreads, each of which features one

poem and a corresponding collage.

The

Dada movement of the early twentieth century has deep ties to the

world of childhood. Its name, though it may have been chosen at

random (the leading origin story involves a knife being plunged

indiscriminately amid the pages of a French-German dictionary), means

“hobbyhorse,” a child’s toy that is an amalgamation of a stick

and a horse’s head. Both parts of the toy are rough approximations

of the real object—a riding horse—they are meant to represent and

this relationship is activated by imagination. The same might be said

of the works created under Dada’s banner. A synthesis of various

media, concepts, and styles, the movement’s visual art and poetry

deconstructed the elements of sound, language, form, color, and

movement and stitched them back together in new ways to create

objects and texts that followed the laws of child’s play—that is,

laws by which any meaning is possible and none is required. This

rejection of adult-world conformity in favor of youthful nonsense

offered a means of circumventing the strict and serious rules that

govern thought, language, and meaning. “I wish to blur the firm

boundaries which we self-certain people tend to delineate around all

we can achieve,” declared Hannah Höch, the Berlin movement’s

only woman artist and an originator of photomontage. Even artmaking

itself was decidedly unsophisticated. Tristan Tzara’s “How to

Make a Dadaist Poem” (1920)—which includes the directives “Choose

from this paper an article the length you want to make your poem. Cut

out the article. Next carefully cut out each of the words that make

up this article and put them all in a bag. Shake gently.”—resembles

the instructions of a child’s rainy-day activity.

Runfast

In

his recent history of children’s literature, Seth Lehrer traces the

exuberant absurdity in the work of authors such as Shel Silverstein

and Dr. Seuss back, by way of Edward Lear and Lewis Carroll, to the

Dadaists and the Russian avant-garde. Yet, unlike their Soviet

contemporaries, the Dadaists produced only a small handful of

illustrated books explicitly for

children. Between 1924 and 1925, artists Kurt Schwitters and Käthe

Steinitz collaborated on three experimental children’s

books—Hahnepeter

(Peter

the Rooster), Die

Märchen vom Paradies

(The Fairy Tales of Paradise), and Die

Scheuche

(The Scarecrow)—all of which depended heavily on typographic

design, particularly the last, which, with the aid of De Stijl

founder Theo van Doesburg, transformed its characters into

typographic forms. (Schwitters also authored a number of other fairy

tales, which were collected and published last year as Lucky

Hans and Other Merz Fairy Tales.)

One

other illustrated children’s book that came out of the Dada group

wasn’t actually created until after World War II. Höch put

together her Bilderbuch,

or picture book, a photomontaged zoological garden accompanied by a

series of sly, silly poems, in 1945. Unfortunately, Bilderbuch

wouldn’t be published in its entirety until 1985, six years after

Höch’s death, and then only in a limited edition of 200. Now,

Berlin publishing house the Green Box has rescued this unique volume

from out-of-print obscurity with a lovely facsimile edition that

reproduces the poems in English translation (courtesy of Berlin-based

scholar Brian Currid).

Picture

Book contains

nineteen horizontal spreads, each of which features one poem and a

corresponding collage. The photographs from which Höch, Dr.

Frankenstein–like, sourced her image-parts are mostly in black and

white. But in each composition, she added brightly colored paper

fibers, whose airy strands resemble feathers—appropriate not only

for the many birds that populate the book, but also for the

extraterrestrial flora and fauna that exist alongside them and Höch’s

other chimeric creatures, who are festooned with tinted tufts. The

picture illustrating the poem “Gentlebread” is almost

Disney-worthy: its rainbow-hued palette enfolds a deer-like creature,

delicate head bowed, who is attended by a coterie of winged friends.

The

hybrid animals are every bit the hobbyhorse—syntheses of diverse

objects that, united as a single image, receive new life in the

reader’s imagination. In one case, Höch uses only slightly trimmed

photographs of Komondor dogs, whose long coats resemble the white,

twisted cords of a mop. Their appellation, Longfringes, mimics their

alien, ropy appearance, but in the context of the book, the animals

become something else altogether. The transformation is aided

by Höch’s brief nursery rhymes; some offer light morals, others

are gently subversive, but all elicit a delightful naivete.

Unsatisfeedle

Flailing

his arms about, quite a sight,

He

had wanted the black dress

But God gave him the white.

So with

his sourpuss

he lives out his life.

He

nurtures the eccentricity

it’s

the wrong one — explicitly.

Brushflurlet

Words

and images are everywhere joined in tomfoolery. Most of the poems’

characters have collaged names: Unsatisfeedle, the Runfast (and her

1,000 runfastlets), Shellkeglet, the Brushflurlet, the

Snipplensnapplewings. In “Meyer I,” Höch tweaks rumor

and

aquarium

so

that they rhyme; the resulting rumourium

and aquorium

share consonants and vowels, each becoming a hybrid of the other. The

image on the facing page likewise adopts a quirky syntactic fusion,

in which something is not quite right: Roughly half of a cat’s

face, open-mouthed, is cut to look like an angel fish, swimming among

jade-green plant life on his way, the poem announces, “to the

office.” The story of the Tailchamois begets a kind of nonsense:

“With their long tails / they sweep away the snow and rime / while

on their mountain climbs. / For they want the winter / to toddle off

a sprinter.”

Of

his fellow Dadaists, Hans Arp once asserted, “We do not wish to

imitate nature, we do not wish to reproduce. We want to produce. We

want to produce the way a plant produces its fruit, not depict. We

want to produce directly, not indirectly.” None of Höch’s

creatures can be said to follow the dictates of nature, though

sometimes they beget a world that appears to be a topsy-turvy version

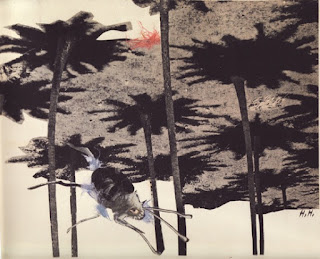

of our own. In the image accompaniment to “The Runfast,” the

titular creature, an insect with a human eye and blue-purple tufts of

fur, skitters under what look like a group of flowers with

starburst-shaped blooms but are in fact the trunks and shadows of

palm trees turned upside down. The irrationality in Picture

Book

isn’t the chaotic, anarchist brand that defines much Dada art, but

rather an innocent version, eschewing machine aesthetics for an

organic sort. Höch’s children’s book also doesn’t offend the

sensibilities, a primary aim of the movement, but it does unleash

them—and perhaps that is the more radical of the two.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario